Overview and core documents

Drawing on examples developed by several institutions, we have developed a decolonisation framework that aims to meet the following principles:

- Sustainable and positive – The process of decolonisation is gradual, complex and requires time and intellectual investment, and in order for it to be effective it must be sustainable for the lecturers who are leading the work

- Transparency and accountability – We wish to share our process, highlighting existing issues, publishing feedback and describing the thought processes and changes being made to the curriculum. This will be productive for the community, and build trust.

- Educators own the process and are acknowledged

- Iterative – decolonisation is a process of self-reflection and interrogation, is continual. Decolonisation activities will be recorded as case studies and highlighted here, to share new ideas with others

- Collaborative – peer review, student review

The framework contains prompts you can use to explore your curriculum. You do not have to complete all of this in one go, and not all of these will be relevant to your field. You can also add more areas of reflection at the end of the spreadsheet, which might tailor this Framework to your topic. If you create new categories which you think are helpful, please feel free to share them with the MART group via the website.

Remember to take your time. Make this an enriching, positive and sustainable process. This is not a task list, this a tool for reflection, one that you have power over and can evolve to suit the needs of your course as your knowledge of decolonisation changes.

Below you will find a section on Peer Review which is an important part of assessing the impact of our work, both positive and negative. The Microsoft form can be accessed via the button below.

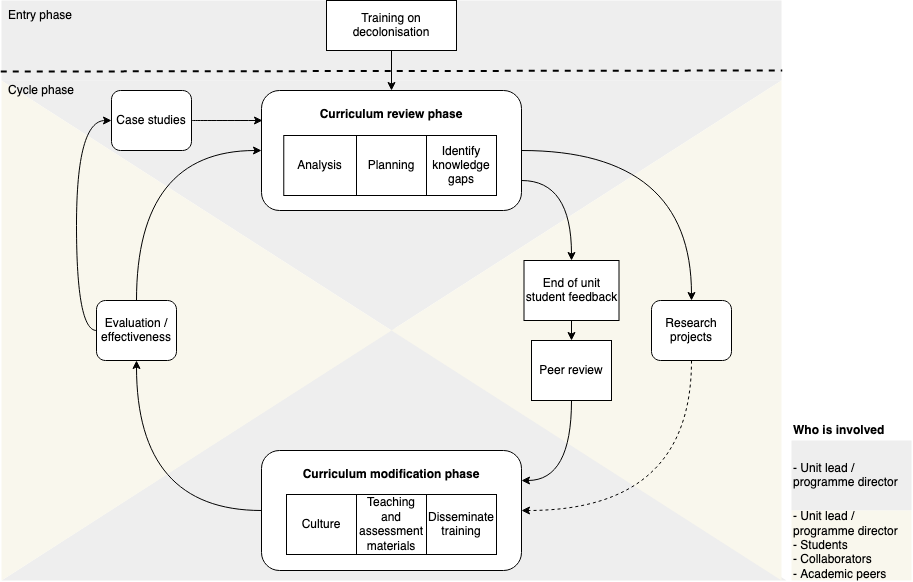

The cycle

A major part of this form of curriculum review is that it should be an on-going process. Much of the theory around decolonisation posits that it isn’t a tick-boxing exercise and it’s not something that you aim to ‘complete’. It is important we continually reflect on the biases that exist and in doing so over time we may become aware of new, previously unconscious biases that warrant further exploration. However, as you progress through cycles of reflection you may notice some previously larger activities become extensive over time, or realise that some changes must be spaced out over multiple cycles in order to make them sustainable.

A schematic of the process is provided here:

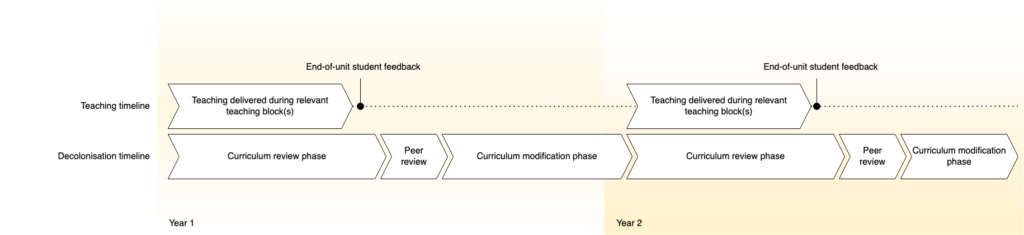

To put this cycle into practice, it is ideally conducted in conjunction with teaching activities as illustrated below. For teaching occurring in teaching block 2, the timeline below might be useful because the curriculum modification phase can be done in time for submission of changes to intended learning outcomes ahead of the January deadline.

For teaching block 1, this timeline might be more drawn out.

Let’s talk through the different components below:

Initial training

Before entering into the work of decolonising your curriculum, it is helpful to gain some training on the core ideas and concepts, and what the process might look like in practice. Please see the Getting Started page for addtional information, including foundational and subject specific content.

Review phase

A major component of decolonisation is identifying the aspects of bias and coloniality that may be embedded within our teaching and research practice. These biases can be overt and immediately obvious, for example a lack of representation of different skin tones in dermatology lectures. The biases could also be subtle, unconscious and inherited from your own educators, and it is imperative that you are given time to be introspective, to honestly critique your own work, and to take ownership of issues that may exist there. Your work may have historical legacies and technical or practical limitations that are entangled with coloniality, and it can be a major intellectual activity to unravel these complexities. Please see the Case studies page for inspiration on aspects of coloniality that others have identified and discussed.

We recommend that a review phase is conducted over the course of delivering the unit. Here you may analyse and reflect upon different aspects of coloniality within the curriculum. You may plan what changes need to be made to remove biases from teaching materials.

You may also identify problems in your field in general. For example there may be a lack of unbiased research on a particular field that could form the basis of a valuable research project. This is a great opportunity to link teaching to research activities – please see the Research page on how this might be done.

Involving students: It is a really good idea to involve students at this stage – it can be beneficial to you, and beneficial to them. However, it is absolutely crucial that this is done in an equitable manner. It is very easy for students to be exploited through their contributions to decolonisation activities. Please see the Student voice page for an outline of how students have specified how to involve them fairly.

Feedback

It is of critical importance that you are supported through the decolonisation process, and this is partly achieved through gaining constructive feedback on your curriculum, and on your own reflections, evaluations and plans from the ‘Review phase’.

This is a great time to gain feedback because you will be able to collate your own reflections with your end-of-student feedback, and you will be able to gain ideas and guidance on what to change prior to actioning any of your plans. This could help make the decolonisation process more sustainable, avoiding misdirected effort, and helping to clarify ideas.

Please see the ‘End of unit student evaliation’ and ‘Peer review’ sections below for more guidance.

Modification phase

Equipped with plans that have been informed by your own reflections, student feedback and the peer review process, the task of making changes to your curriculum should now have greater clarity. We would encourage that changes are made in three main areas

- Your teaching and assessment materials, including intended learning outcomes, and data and resources being used throughout the course

- Ensuring that tutors and lecturers who contribute to your course have had adequate training on relevant aspects of decolonisation

- Cultural changes to your teaching, which may include teaching styles, assessment styles, being more inclusive in selecting those who contribute, and approaches to handling sensitive topics

Evaluation and effectiveness

Through your decolonisation work you may identify limitations or gaps in the current framework being provided. This could be in terms of the need for more teaching and training materials on decolonisation, or the framework itself. We strongly encourage feedback to us about how effective you feel this framework is, and where improvements might be made.

We also strongly encourage you to contribute to the Case studies page. Case studies can be positive outcomes from reflections and modifications, or lessons learned from past activities or attempts to implement decolonisation actions. Your experiences may help others to think differently about their teaching.

The cycle continues

Your modified curriculum will now feed into the next iteration of your teaching. You will have an opportunity to further reflect on your curriculum. You may identify new biases that you had previously not been aware of. There may be developments in your field that raise new problems. There may be decolonisation activities that you have previously de-prioritised to ensure that the process is sustainable.

Following this second round of review, you will have the opportunity to compare student feedback and to the previous year, and to debrief with your peer reviewer regarding changes made previously.

End-of-unit student feedback

The student feedback process is a key part of any unit or programme. End of unit feedback systems and question banks may differ across courses, however they provide an excellent opportunity to gather feedback and insights into aspects relating to coloniality within your course.

A suggested question bank to include in feedback forms is below, which is designed to help with your decolonisation process.

Suggested introductory text:

This Unit is undergoing decolonisation, and as a student who can access a copy of our ongoing plan for this work here [insert a Blackboard link to your Framework outline]. The following questions are optional but helpful for us to understand more about this process and what work we still need to do:

Suggested question bank:

| The understanding and skills I have gained from this unit apply to diverse ethnicities and populations |

| During this unit I feel I have been exposed to a demographically and geographically diverse set of authors, researchers, and theorists |

| Controversies in the field of studies have been explored and I feel I have a critical awareness of the topic and its history |

| This unit has equipped me with a global awareness of the discipline and its impact |

| Conversations around ethnicity, religion, gender, sexuality and other marginalised identities have been handled respectfully and with care |

| Tokenism is avoided, and inclusion of marginalised identities within the teaching has been done is respectful, avoiding harmful stereotypes |

| I have felt able, or would feel able, to raise issues around harassment, discrimination or bullying with staff on this unit |

| The content of this unit has been accessible |

N.B. Receiving student feedback is a fundamental part of pedagogy in general. To gain high response rates it is highly recommended that you create allocated time in class specifically for student feedback – either to fill in end of unit forms, or for discussions etc.

Peer review

Gaining feedback from peers in your field provides an opportunity to discuss aspects of coloniality at a higher technical level than you might be able to do with students or experts in coloniality who are not part of your field.

We suggest you undergo peer review after the completion of the ‘review phase’ of the decolonisation framework, and after you have received end-of-unit student evaluations. This peer review process will then help guide changes that to the curriculum that will be made during the ‘modification phase’ of the decolonisation framework.

Effective peer reviewers will be those who have some expertise in your field and may have had exposure to ideas around decolonisation activities before. They can be internal or external to the University.

Please provide reviewers access to the following:

- Your teaching materials

- Your decolonisation framework with at least the ‘Reflection’, ‘Prioritisation’, and ‘Planned actions’ sections completed

- End-of-unit student feedback (ideally including a question bank on decolonisation).

The peer review process should be constructively critical, to aid with implementing changes to the course during the ‘curriculum modification phase’ in a more effective and optimal manner.

Evaluation

The decolonisation process can be a major undertaking, and there are numerous ways in which it can be approached. The Centre for Health Sciences Education will devise approaches to monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of this decolonisation framework, and transparently report results on a regular basis.

We will update this page as frameworks are put in place to conduct framework evaluation.