What is decolonising the curriculum?

A curriculum provides a way of identifying the knowledge we value. It structures the ways in which students are taught to think and talk about the world. Our curriculums can be tremendously impactful to students themselves, and to the people with whom they come into contact throughout their lives.

In a colonised curriculum the world view presented to learners predominantly belongs to a white, male, affluent, European perspective (Charles 2019).

More broadly, we can think of Universities as being institutions that generate, store and disseminate knowledge (Collini 2012). A university being ‘colonised’ in this context implies that structural filters exist on what knowledge is generated, what knowledge is stored, and what knowledge is disseminated. It implies that there is a bias that informs what we count as valid knowledge.

The consequences can range from affecting our students’ experiences, to reinforcing structural biases impacting health and society.

In the context of the medical school:

- Student educational attainment gap

- Reputational risk

- Patient safety

- Health inequalities

- Research quality

- Representation and retainment of marginalised groups

What decolonising the curriculum asks us to do is to analyse these biases, and make changes to remove them. Decolonisation builds upon ideas of inclusiveness by thinking about the causal structures that led to the biases in the first place.

Decolonisation is disruptive, but that isn’t inherently bad

The process of decolonisation deliberately disrupts the systems and assumptions on which we have built our teaching. In many ways it is important that we become comfortable with the feeling of discomfort such re-examinations can generate, as if decolonisation was entirely comfortable it is unlikely we are being reflective enough.

Decolonisation should be a positive and liberating experience that benefits all. We have an opportunity to intercept the transmission of biases that we ourselves may have inherited. Our students are the future owners of our respective disciplines. It is our responsibility to equip them with the ability to identify and deal with biases within our fields. This can only be achieved by analysing ourselves, our work, our teaching, our field, and taking ownership of the issues that we might find and facing them head on.

How to use this website

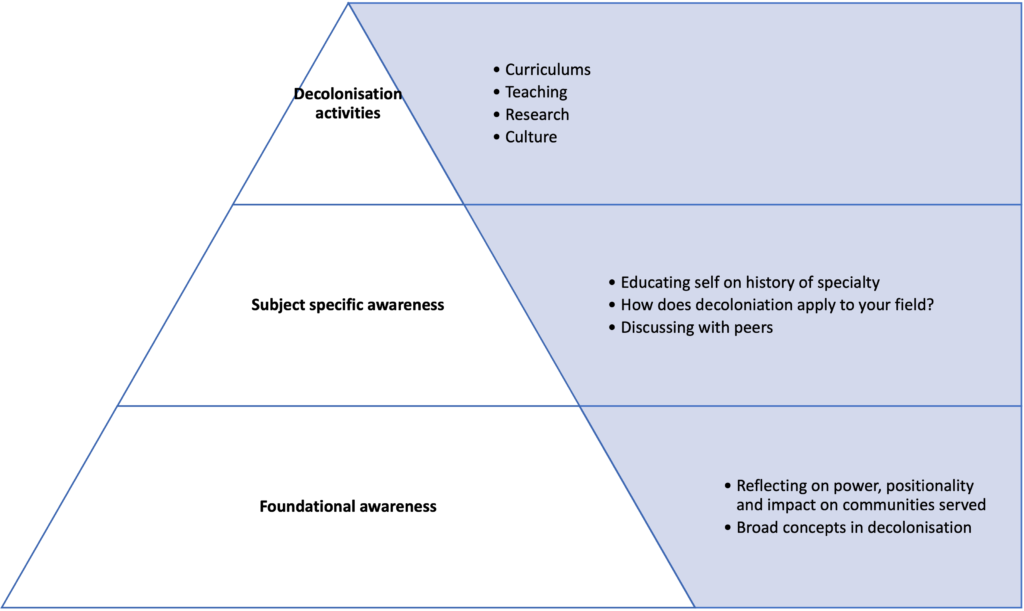

This website aims to guide educators in BMS through a suggested decolonisation framework. An overall conceptual framework is shown here:

We need to recognise the interplay between individual learning and growth and the systemic and institutional changes needed to advance antiracist policies and practices. Therefore, we recommend the following approach

Step 1 – foundational awareness

Find resources on unconscious bias, bystander training and introductions to coloniality on the Foundational Awareness page below

Step 2 – subject specific awareness

Educate yourself by researching what is being thought about in terms of bias and coloniality in your specific field. The Subject Specific Awareness page has a (growing) list of resources that might help you get started, but it’s pretty small at the moment. Do help us grow this resource!

You can also take inspiration from Case Studies of previous decolonisation work within BMS.

Step 3 – decolonisation activities

We have developed a Framework to guide your on going decolonisation activities. Essentially, it is a set of prompts that asks you to note down your reflections on the current form of your curriculum. You can than plan changes, get feedback from peers and students, and execute those changes. We want this to be a positive, transparent and sustainable process. We want you to be recognised for this work.

Further steps

Through analysing your curriculums, you may identify new research opportunities within your field. See the Teaching-Research Nexus page on how you can link these activities.

Contribute your own Case study.

We’re continually trying to improve this website, its resources and the framework, so please do provide feedback to ensure decolonisation work is effective.

Frequently asked questions

Here we have tried to answer some of the frequently asked questions we have heard when developing this resource for BMS. These are not exhaustive, but we hope they are useful.

What are some examples of biases in relation to medicine?

Recent studies have highlighted that systemic racism persists in the NHS for both staff and patients (BMJ 2020). There are health inequalities in the UK that are plausibly due to racism (BMJ 2019).

Despite calls from major journals, adequate research on health inequalities has failed to materialise (Salway et al 2020), suggesting that research itself is colonised. Some specific examples are listed below

- Perceptions of Black people’s experience of pain and the impact on prescribing (Goyal et al (2015), Hoffman et al (2016))

- Increased maternal mortality in Black women (Anekwe (2020), cdc.gov (2019), Creanga et al (2017), MBRRACE–UK (2018))

- Different survival rates in Black children when cared for by White vs Black clinicians (Greenwood et al (2020), Mahase (2020))

- Differences in the experiences and outcomes of racialised people’s mental health in the UK (raceequalityfoundation.org.uk (2019))

- Examples of the exploitation of racialised people in medical research, such as the Tuskegee Syphilis Trials (cdc.gov (2020), Duff-Brown (2017))

- The South Asian population, particularly women, have lower screening rates for breast, cervical and bowel cancer. Poorer awareness of risk factors for cancer and symptoms, and socio-cultural and practical barriers such as language contribute to this. Health promotion needs to be accessible and inclusive. (Kingsfund, 2021)

- Exploring the lack of diversity and understanding barriers to participation in clinical trials. Examples might include poor individual representation in studies or the use of predominant European ancestry data in cutting edge genetics work

- The vast majority of European studies (as of 2021) are conducted in individuals of European ancestry (https://gwasdiversitymonitor.com/), even in diseases that predominantly influence non-Europeans (Conti et al 2021), and with knowledge that genetic results from Europeans won’t necessarily translate to non-Europeans (Márquez-Luna et al 2017).

Finally, there exists a large and persistent racial attainment gap that cannot be explained by factors other than race (Woolf et al 2013, Shah and Ahluwalia 2019).

Why ‘decolonisation’ and not ‘inclusiveness’?

‘Inclusiveness’ has been an important part of curriculum design for decades. ‘Decolonisation’ does ultimately wish to challenge exclusions (of particular types of people, ideas, knowledge, practices etc), and so these two movements have the same aim. Decolonisation emerged as a theoretical framework that imposes a causal structure for why problematic exclusions exist today.

Therefore, decolonisation asks you to analyse the causes of the biases you might find in your curriculum in order to more effectively address them.

So how does decolonisation relate to other equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) work?

Decolonisation work is similar to EDI work focused within education, but it is more than simply expanding representation within the content of what we teach and who teaches it. It is possible for us to be inclusive without decolonising.

EDI work, especially curriculum work, can often feel tokenistic. This occurs when we fail to address the root cause of the original exclusion, and present only the more palatable forms of inclusion. Often these ignore intersection of identities, and seeks to keep as close the societal “norm” as possible.

We must also consider the hidden curriculum which upholds a complex paradigm of stereotypes, biases and behaviours which dictate what success within our discipline looks like. It is not enough to simply diversify the content of our teaching; this must be done authentically with research into cultures and identities that avoids falling back on lazy stereotypes. Although discussions around race and ethnicity are vital to decolonisation, it is not limited to these topics.

How does decolonisation in the health sciences differ from other subject areas in the university?

Biases manifest in different ways between disciplines and geographical contexts, and the set of causes for and consequences of bias can be varied. Therefore, the emphasis of activities can change slightly from one course to the next.

In a recent review of more than 200 publications on decolonisation work, Shahjahan et al (2021) noted that more applied subjects, such as those in science and medicine, need slightly more emphasis on asking “who is the curriculum for?“. This is in contrast to the more traditional question of “who the curriculum is by?“, which is where focus is needed in more humanities oriented subjects.

For example, in Genetics we might ask whether we are teaching our students to be able to analyse genetic data from diverse ancestral backgrounds, because if they are only taught how to analyse datasets of European samples then therapeutic potential may be exclusionary.

Who is responsible for decolonisation?

Everyone is responsible for decolonisation, however within this framework we have put a lot of the emphasis for change on the lecturers and educators who are creating and delivering curriculums. This does not mean student voices should be ignored, and you can visit our “Student Voice” page to see suggestions from students on the ways in which they can be engaged in this work. However, it is important that students do not drive this work alone, and historically this has often been the case. We hope that this website and framework will empower medical and science educators to feel they can lead these changes in partnership with students.

What are the advantages of decolonisation?

The advantages of decolonisation are theoretically numerous but often hard to measure. There is a lot of research which demonstrates racial disparities in medicine. However, the evidence to support decolonisation can be harder to find, especially in the field of medicine and its related sciences. There is certainly evidence for racism within the NHS itself in various forms (Adebowale and Rao, 2020) and the BMJ has a collection of articles exploring the topic of racism in medicine you can access here. Despite calls from high profile journals, adequate research has failed to materialise that interrogates this in depth in the UK (Salway, 2020). The field of genetics research, which will inform much of the wider work within medicine, can strongly attest to this lack of interest, with the vast majority of genetic studies focusing on European subjects (GWAS Diversity Monitor, 2021).

This paucity of evidence in the field of health sciences makes it a prime ground for research opportunities. Nevertheless, from the evidence that exists in other academic fields, and from the ingrained issues of systemic racism in healthcare, we can extrapolate some of these benefits. Decolonised curriculums are more inclusive of marginalised groups, especially on the topic of race and ethnicity, and this improved representation in key teaching (such as clinical signs in different types of melanated skin) can have real world benefits for patient safety. In addition, promoting conversations around inclusion can improve the applicability of research to the diverse communities we serve, and help prevent students establishing unhelpful biases early in their professional identity formation. This in turn can help tackle some of the causes of systemic health inequalities that we see affecting marginalised communities. Finally, diversifying our curriculums allows students to better see themselves represented in teaching, which is associated with an improvement in awarding gap data.

These are only some of the benefits and assessing the impact and effectiveness of decolonisation is something we encourage our staff to consider in the planning of this work.

I have used the Framework, have I now completed decolonisation?

The short answer is no. The decolonisation framework has been designed to be a cyclical process of reflection and implementation, as we assess the impact of our work and make further changes. Decolonisation is not a checklist process. It does not end, but is a constant re-examination of our teaching content and culture. In the same way that curriculum review processes ensure that we do not stagnate in our teaching, decolonisation approaches might will change and evolve over time as more evidence emerges.

Is the framework a checklist?

No. In many ways it might resemble a checklist to decolonisation, but this is not its purpose or how it should be implemented. This is a series of prompts to aid reflection. You do not have to complete them all, and you should definitely add your own to expand the opportunities for reflection to be more specific to your teaching. Your prompts and reflections should be revisited, explored and assessed for impact. No category can simply be “checked off”.

What is the medical anti-racism taskforce (MART)?

Following the global anti-racism protests of 2020, the BAME Medical Student group at BMS wrote to the School Executive Committee asking what the plans were to decolonise the curriculum. In response, the School outlined a commitment to building sustainable anti-racist practices. In partnership with students it was agreed that the Medical Anti-Racism Taskforce would be formed to helped drive these changes under different topics which demanded a focused agenda. You can read more about this on the Medical Anti-Racism Taskforce (MART) Sway. MART consists of researchers, educators, students and professional services staff who volunteered into the group, and this website has been built by the Special Interest Group focusing on Diversification and Decolonisation.

Do I have to change my whole curriculum?

No, decolonisation does not require you to change your whole curriculum, but depending on the current content you might change a little or a lot of it, and you might have to reframe some of the ways you present information. This might include highlighting historical injustice or points of controversy, or it might be bringing attention to scholars in your field who have previously been ignored. We are not looking to eliminate core teaching, but instead seek to ensure that teaching is delivered with acknowledgement of the underpinning social and historical context of our topic.

Is decolonisation just about race?

It would be simplistic and unfair to describe decolonisation as just about race, although exploring racism and race is an integral part of the process. Instead decolonising medical sciences should explore under represented groups missing from our curriculums, and the nuanced intersectionality that is often lost in healthcare teaching.